Texts

CHILEAN ART: A CONTEMPORARY LABORATORY OF IDEAS

Christian Viveros-Fauné

Laboratory

1 a : a place equipped for experimental study in a science or for testing and analysis // a research laboratory

broadly : a place providing opportunity for experimentation, observation, orpractice in a field of study

1 b : a place like a laboratory for testing, experimentation, or practice // That area is a laboratory for cultivating the germ of terrorism1

Sometimes the ironies of history are too much.

So it is with one of the most fascinating chapters of the short-lived government of Salvador Allende. Shortly after taking office as president of Chile in November of 1970, Allende began to nationalize key industries like copper, coal mining, agriculture and the banking sector. Along with these macroeconomic steps, Allende promised increased worker participation in planning what he called “the Chilean road to Socialism.” To fulfill both of these goals he headhunted a legendary British consultant named Stafford Beer to apply the theories of cybernetics—first defined in 1948 as “the scientific study of control and communication in the animal and the machine”2 —to the management of Chile’s state-run economy.

Beer’s mission was intended to be both everyday practical and techno-utopian: to deliver a state-of-the art information system that could rationalize economic decisions for Chile’s economy—via networked telex machines and state-of-the-art software that would keep track of real-time economic indicators, shortages, factory output, consumer demand and so on—in order to usher socialism into the computer age. The resulting management system was christened Cybersyn. An appropriately sci-fi portmanteau for the terms “cybernetics” and “synergy,” the project aimed to coordinate a national command economy, but also to track data that would directly serve the well being of Chileans throughout the length of the country’s 4,270 kilometers.

At the center of Project Cybersyn was the physical construction of the system’s operations room. Engineered by German design theorist Gui Bonsiepe and constructed as an actual prototype inside the interior courtyard of Chile’s national telecommunications company in downtown Santiago, the structure’s HQ described a hexagonal space, thirty-three feet in diameter, accommodating seven white swivel chairs with orange cushions and four futuristic screens on the walls. These were, in turn, connected to 500 reporting Telex machines distributed around the country in important factories.

More than one commentator has compared the design of Cybersyn’s Operations Room to the bridge in the television series Star Trek. Instead of windows into the galaxy, though, several of the room’s screens were set to display a steady datafeed of information on national production. Remarkably, one panel was reserved for an even more visionary concept: Project Cyberfolk. An ambitious effort to track the real-time wellness of the entire Chilean nation in response to government policies, Cybersyn proposed that a voltmeter-like device be installed inside every Chilean home to transmit the nation’s satisfaction at any moment, live and instantaneously, through existing TV networks.

No mere sci-fi dispatch from the future, Project Cybersyn anticipated the beginning of today’s use of computers by our hyper-linked, consumer-desire economy—Amazon’s “anticipatory shipping,” Google’s search ads, and Uber’s entire business model—as well as a flood of new corporate and government schemes to collect and analyze information in real time. One, of course, does not need to be a close reader of Hegel to imagine that every utopian proposition contains its own antithesis. More than just the “socialist origins of big data,” Project Cybersyn can also be said to have predicted it’s opposite: the seeds of information glut and the surveillance state.3

Which is precisely how the equivocal legacy of Project Cybersyn manifests in Mario Navarro’s Red Diamond (2006). A three-dimensional sculpture that flatly holds in abeyance—as only a work of visual art can—both the possibilities of social progress and its dystopian possibilities as these apply to a country in a state of continuous development (or underdevelopment, as the case may be), this diorama- like construction also contains trace elements of a national idiosyncrasy, at least as applied to the evolution of Chile’s visual arts: the overwhelming tendency of the country’s best artists to define their proper field of operations as a global laboratory of ideas.

If there is one thing academics of both the Left and Right agree on, it is that Chile has served as the world’s social and economic laboratory for more than 50 years. This is certainly how Chicago University trained Chilean economist Sebastián Edwards characterized the country in his book Monetarism and Liberalization: The Chilean Experiment. “The study of Chile’s modern economic history usually generates a sense of excitement and sadness,” he wrote in 1991. “Excitement, because from 1945 to 1983 Chile has been a social laboratory of sorts, where almost every possible type of economic policy has been experimented. Sadness, because to a large extent all these experiments have ended up in failure and frustration.”4

In 2007, author and activist Naomi Klein painted a much bleaker picture of Chile as a test case for various social and economic theories of global importance. In her book The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism, Klein chronicles how the country became the primary proving ground for a “shock program” of sweeping neoliberal reforms that included the privatization of state-run industries, the elimination of trade barriers, and cuts to government spending—with their ensuing crippling social effects. To implement these unpopular policies, Klein says, Chile became “a laboratory for these radical [free market] ideas, which were not compatible with democracy in the United States but were infinitely possible under a dictatorship in Latin America.”5

As both Edwards and Klein point out, Chile has been the site of dramatic change and experimentation for some six decades and counting. Socially and economically, but also culturally, the nation’s eighteen million people have served as experimental subjects for some of the world’s most pivotal civic experiments. Among these are President Eduardo Frei’s “revolution in liberty” (1964 to 1970), Salvador Allende’s “Chilean road to socialism” (1970-1973), Augusto Pinochet’s “silent revolution” (1973- 1989), and the seesawing reforming efforts of seven successive democratically elected progressive and conservative governments that have chaperoned the nation’s “eternal transition” from military to civilian rule. As one commentator wrote about the state of play in Chile since 1990: “the country may have returned to democracy, but it will be a long time recovering from its experiments.”6

But Chile presents another, more enduring face to the world: namely, its rich symbolic production. If it’s possible to view the modern history of Chile, together with its most important attendant cultural and artistic developments, as a post-WWII social laboratory for the global North, it’s also possible to make certain special claims for its visual art. Beginning with a provincial-modern tradition that, in the words of Andrea Giunta, interiorized the vanguardist model of artistic production via a set of unique temporal, geographic and cultural contexts, several generations of Chilean artists have learned to establish simultaneous patterns of discovery with their U.S. and European homologues.7 The fact that some of these same artists have, in the process, privileged certain lessons from their chronically unstable scenarios suggests that, in important cases, they have also regularly anticipated key insights and discoveries for the rest of the world.

Starting with the group of artists that critic and theoretician Nelly Richard christened the “Escena de Avanzada” in her book Márgenes e Instituciones: Arte en Chile desde 19738—among them Lotty Rosenfeld, Juan Castillo, Carlos Leppe, Juan Domingo Dávila and the members of the art collective Colectivo Acciones de Arte (C.A.D.A.)— contemporary creators in Chile began to incorporate novel discourses from the global north to adapt and even retrofit to their local circumstances. Among these newfangled artistic concepts were U.S.-style performance art (as exemplified, say, by Yoko Ono’s Cut Piece, from 1964), body art (Carolee Schneeman), happenings (Allan Kaprow) and land art (Robert Smithson), as well as the writings of French poststructuralist authors like Roland Barthes, Jacques Derrida and Jacques Lacan. These ideas filled the air in the U.S. and Europe like weed pollen in the late 1970s and ‘80s; in Chile, the same allergens produced markedly different reactions.

Instead of merely repeating the overwhelmingly apolitical results produced by artists in New York and Paris, the “Escena de Avanzada” modified certain postmodern and poststructuralist precepts to expose urgent new contradictions. C.A.D.A.’s members (sociologist Fernando Balcells, novelist Diamela Eltit, poet Raúl Zurita and artists Juan Castillo and Lotty Rosenfeld), for one, staged a multi-part performance aptly titled Para no morir de hambre en el arte [In Order To Not Starve to Death In Art] (1979) at the height of the Pinochet nightmare. A protean event that consisted of several actions calling attention to the problem of hunger at a time when 36% of Chileans lived in poverty—passing out milk to people in Santiago’s slums; parading milk trucks through the city’s streets; calling attention to these events with full-page ads in periodicals; declaiming the group’s message in front of the local United Nations building—their intervention successfully harnessed the symbolic power of visual art to represent an otherwise unrepresentable political demand.

That same annus horribilis, Lotty Rosenfeld, a founding member of C.A.D.A., staged Una milla de cruces sobre el pavimento [A Mile of Crosses on the Pavement] (1979) on Santiago’s Avenida Manquehue. The film and photographs that document the intervention show the artist kneeling on a roadway and cutting pieces of tape (or are they bandages?), which she then subsequently adheres onto the road’s dividing lines in the form of crosses. Age-old symbols of suffering and death as well as startling subversions of standard traffic markings, Rosenfeld’s bisecting lines also periodically adorned the streets of cities like Washington, London, Paris and Madrid during the artist’s performances from 1980 to 2009. A now legendary gesture of protest, Rosenfeld’s interventions also constitute an urgent call to reexamine common symbols—while allowing for their meanings (their politically charged positivity or negativity) to shift dramatically according to a given territory’s respect for civil liberties.

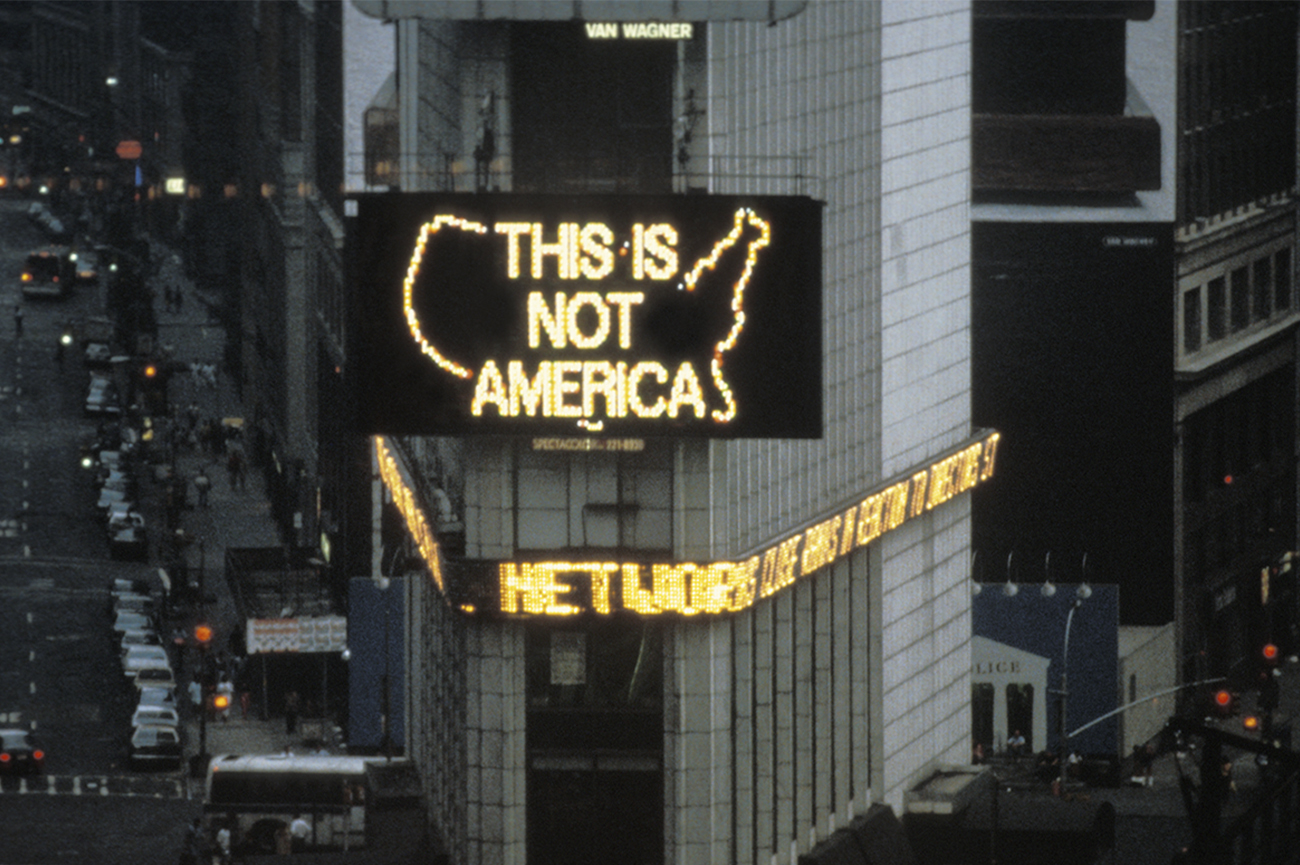

As Brazilian polymath Hélio Oiticica once said in relation to Latin American artists: “We live by adversity!”9 That adversity, understood as a near constant state of emergency, has produced a series of crucial reinterpretations of what was once a dominant U.S. tradition of politically agnostic conceptualism—as seen, for instance, in Joseph Kosuth’s series Art As Idea As Idea (1966-1967). In April of 1987, the flip side of that tradition went up in lights in the heart of New York City: Alfredo Jaar’s A Logo For America was displayed on Times Square’s Jumbotron. A 45-second light animation combining images of a glowing U.S. map, the American flag and the words “This is Not America,” the celebrated work turned a flat proposition—not unlike René Magritte’s painting This Is Not a Pipe—into a hemispheric political provocation. Conceived after several decades of U.S. interventionism in Latin America, the work’s relevance has only grown at a time when North American ethnocentrism has morphed into its blood cousin: anti-immigrant bigotry.

In societies like Chile that undergo regular political, social and economic upheavals, the streetwise merger of art and life that artist Robert Rauschenberg evangelized in the U.S. was bound to look and feel different (according to critic Guillermo Machuca, the American artist’s controversial 1985 visit to Chile contributed, among other events, to the closing of the “Escena de Avanzada”10). So it was with Paz Errázuriz’s photographs of transgender and transvestite communities living on Santiago’s hidebound margins. A document of political and sexual history under authoritarianism, Errázuriz’s series La Manzana de Adán [Adam’s Apple] (1982-1987) captured Chile’s gender revolt straight, no chaser. Her pictures also proposed the opposite of detached observation favored by conventional documentarians. Shot mostly in black and white, Errázuriz’s images constitute a celebration of sex, strangeness, resistance and survival. As the artist told one interviewer about the years she spent embedded with her subjects: “I witnessed it all, and through photography I perpetuated their rebellion.”11

Thus was the contemporary bedrock of Chile’s artistic alterity laid down, one socially inspired artwork at a time. When Juan Downey presented his diaristic video The Laughing Alligator (1979)—his highly personal search for an indigenous cultural identity among the Yanomami people of Venezuela—artists like the painter Jorge Tacla, then in his third year of a 39-year New York City residence, unwittingly picked up the baton. While always in negotiation with various territories affected by war, disaster and civilizational collapse, Tacla’s paintings have, after years of nominally depicting Chilean landscapes, come to focus on so-called international troublespots: Lebanon, Haiti, Syria and, of course, the U.S. Consider a painting like La distribución de los primarios [The Distribution of the Primaries] (1995). An aerial view of the Pentagon as both a locus of global violence and the site of future ruin, the canvas also features the artist taking stock of his own situation (and the viewer’s) as the naturalized son of a country with a tragic human rights record and a terrifying global reach.

The history of ideas is the history of their displacement. Together with Tacla, younger artists like Francisca Benítez, Felipe Mujica, Iván Navarro and Rodrigo Valenzuela have also used their voluntary exile in the U.S. to expand the parameters of their practices. Chile is never far from their minds; neither are ideas about how to push the boundaries of conceptual art. Efforts that trade in both aesthetic and social concerns, their eccentric artworks—Benítez’s videotaped explorations of the choreography of deaf poetry, Mujica’s mashups of embroidery and art history, Navarro’s text and neon lit infinity mirrors, and Valenzuela’s staged photographs of real life barricades— all run counter to the idea that advanced art should prioritize formal critique over social criticism. In the words conceptual art pioneer Hans Haacke used to describe his recent museum exhibition All Is Connected: “Experience tells us that one should never leave politics to the politicians. Aside from the trouble this can get us into, such abdication would also be in conflict with generally held notions of democracy. But it would also be dangerous for art. Shutting out the social world would reduce it to a self-consuming art for art’s sake.”12

Thanks to increased global mobility, Chilean artists living in other latitudes have also distinguished themselves as keen social critics in the mold of Haacke. In Madrid, Patrick Hamilton has continued his sweeping exploration of the history and aesthetics of neoliberalism—or as he terms it “the aesthetics of underdevelopment”—as exemplified by his large-scale installation Proyecto Santiago Derivé [The Santiago Derivé Project] (2006–08). In London, painter Francisco Rodríguez has devised a pictorial imaginaire that combines, among other elements, turn of the 19th century Romantic figures, 1980s manga comics, and penumbral visions of Santiago that invoke an elegiac paradox—daytime nocturnes. In Paris, filmmaker Enrique Ramirez has used the language of cinema to arrive at moving image poems that, while recalling the plays and films of Samuel Beckett, feature the holy trinity of national subjects: the recurring themes of memory, exile and exodus.

And then there’s the colossal work that longtime Barcelona resident Fernando Prats exhibited at the 54th Venice Biennial. A 52-foot neon sign he first installed in Chile’s Antartic territory, Prats’ piece directly echoes explorer Ernest Shackleton’s 1911 advertisement for volunteers to accompany him on a treacherous trip to the Antartic: “Men wanted for hazardous journey, small wages, bitter cold, long months of complete darkness, constant danger, safe return doubtful, honor and recognition in event of success.” Then as now, Shackleton’s phlegmatic text forebodes not just the risks of a perilous exploration but the potential of a life-altering passage: the promise of a Gran Sur or Great South.

Finally, of course, there are the artists for whom Chile constitutes not just a prism with which to see the world, but a primary residence. They range from the late Juan Pablo Langlois, a maker of low-tech, stop-motion Dantean daymares, that admix newsprint, sex and violence, to thirty-something Pilar Quinteros, whose videotaped burning of cardboard buildings announces Mapuche territorial claims; from Arturo Duclos’ semiotically-inspired hanging textiles (one of which ominously reads, Arbeit Macht Frei, in imitation of the gates of Dachau), to Francisca Aninat’s fragmented cloth strip outline of the South American continent. Their work, alongside that of artists like Voluspa Jarpa and Camilo Yañez—the former grounds her multimedia work in the meticulous study of declassified archives, while the latter has long studied how politics manifests itself formally—interrogates both history and its representations. In doing so, these creators and others have helped write the recent story of Chilean art and its reception for more than three generations.

Since the mid to late 1970s, Chile’s most important artists have followed a road largely predicated on analysis and experimentation, a path at once committed to a critical rereading of politics yet suspicious of utopian promises. What began with the “Escena de Avanzada” has, in the 21st century, become a family tree populated by probatory, analytical oeuvres, each with its own aesthetic and thematic concerns. Among the themes these various bodies of work engage are: the effects of political repression and its impact on the social body (Elías Adasme, Álvaro Oyarzún), the official legacy of authoritarianism (Andrés Durán, Catalina González), the global effects of neoliberalism (Nicolás Franco, Hoffmann’s House), the precarization of labor (Magdalena Correa, Alejandra Prieto, Camila Ramírez), the impact of scientific and industrial development on the natural world (Adolfo Bimer, Museo de Historia Natural Río Seco), the distortions caused by the information revolution (Cristóbal Cea), and the place of contemplative art in times of great instability (Natalia Babarovic, Mónica Bengoa, Josefina Guilisasti).

Individually and together, the works of these artists point to a wide-ranging economic, political and epistemological crisis that has, in our time, overwhelmed governments and institutions all over the globe. In the words of one of the voices featured in Yáñez’s three-channel video Poética, podredumbre y polyvisión [Poetics, Putrefaction and Polyvision] (2018-2019), “one can see constant similarities in politics and nature.” In Chilean society, the place where nature and politics most sharply diverge is where humans appear to be the only species capable of wrecking their own habitats for the sake of profit, power or both.

These are the artworks and the artists represented by Gran Sur: Contemporary Chilean Art from the Engel Collection. The largest display of Chilean art ever celebrated outside the country, it includes nearly one hundred artworks produced by 13 women, 21 men and three art collectives. Made up of objects and images using every sort of media and on nearly every kind of support, Gran Sur also displays one of the most characteristic features of Chilean art: an alterity that is made both privileged and eccentric by geographic isolation.

As an exhibition and a book, this event also takes place on the heels of a major revolt in Chilean history: the mass protests of October 2019. That crisis speaks volumes about what’s transpired and what’s to come. At the time of this writing—and for the foreseeable future—the story of Chile as a social laboratory for the world is not finished, and neither is the evolving tale of Chilean art.

1 Merriam-Webster Dictionary, s.v. “laboratory,” accessed October 24, 2019.

2 Norbert Wiener, Cybernetics; Or, Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1948).

3 Greg Grandin, “The Anti- Socialist Origins of Big Data,” The Nation, October 23, 2013, www.thenation.com/article/anti- socialist-origins-big-data/.

4 Sebastián Edwards, Monetarism and Liberalization: The Chilean Experiment (The University of Chicago Press, 1991), 1.

5 “The Shock Doctrine: Naomi Klein on the Rise of Disaster Capitalism,” Democracy Now!,

www. democracynow.org/2007/9/17/the_ shock_doctrine_naomi_klein_on, September 17, 2007.

6 Steven Kangas, “Chile: The Laboratory Test,” http://www.huppi. com/kangaroo/L-chichile.htm.

7 Andrea Giunta, “Escenas Simultáneas,” Glosario de Arte Chileno Contemporáneo, October 17, 2018,

http:// centronacionaldearte.cl/glosario/ vanguardias-simultaneas/.

8 Nelly Richard, Márgenes e Instituciones: arte en Chile desde 1973 (Metales Pesados, 2014).

9 Eduardo Baez, Cruelty and Utopia: Cities and Landscapes of Latin America (Princeton Architectural Press, 2003), 200.

10 Guillermo Machuca, “Escena de Avanzada,” Glosario de Arte Chileno Contemporáneo, October 17, 2018,

http:// centronacionaldearte.cl/glosario/ escena-de-avanzada/.

11 Irina Bakonsky, “The Photographer Who Documented the Underbelly of Chilean Society,” Another Magazine, April 13, 2018, www.anothermag.com/ art-photography/10759/the- photographer-who-documented- the-underbelly-of-chilean-society/.

12 Hans Haacke, wall text at New Museum retrospective “Hans Haacke: All Connected,” October 24, 2019 through January 25, 2020, New Museum, New York.

Fundación Engel © 2020

Fundación Engel © 2020