Texts

ARTWORKS THAT BRING CHILEANS TOGETHER

Juan José Santos Mateo

The tall, slim 24-year-old young man exploded with rage. On May 1, International Worker’s Day, he was arrested for defending a boy who was being beaten by a plainclothes policeman. They threw him into the boot of a car and rode around for half an hour until they arrived at the station, where they put him in line with other detainees. They pointed a machine gun at him. After being interrogated, he was blindfolded and taken somewhere on the outskirts of town. Finally, he ended up in prison, where he was kept for nine days. Meanwhile, his mother searched for him desperately. Even in the morgue.

On Chile

When he was released from prison he realized that he was not free. That was when he decided to carry out an action that would denounce repression and the violation of human rights by means of a metaphor. He wanted to intervene in the public space of an intervened country. His intention was to carry out an art action in a subway station whose name was meaningful; he chose one called “Las Rejas,” with its connotation of prison bars, but strong winds put paid to his idea. His second option, “Salvador,” was more fitting. He hung himself upside down from the subway pole outside the station, dressed only in jeans, with a map of the country hanging alongside him, as long and slender as himself. Suddenly a group of cadets from the Military School emerged from the station. Silence fell over the scene until one of them said: “Dude, this is an advertising stunt for jeans.” The laughter eased the tension of the asphyxiating, sinister, threatening atmosphere. We are in Spain, in 2020, recalling an action in Chile during 1979 that lasted just a few minutes. The work is called A Chile (For Chile), and the artist, Elías Adasme, would spend the rest of his life outside his home country.

In Gran Sur: Contemporary Chilean Art from the Engel Collection the viewer may find some emblematic pieces that belong to art history, works that engage with Chile’s dark past, with its flawed transition to democracy and the social, political and economic problems that plague the nation at the present moment (many of the struggles addressed in works by Adasme, C.A.D.A. or Lotty Rosenfeld foreshadow the uprisings Álvaro Oyarzún refers to in his paintings Última parada (Last Stop) or Llegó marzo (March Arrived), both from 2017, which could also have been painted during October of 2019). Though they contrive to fashion a national imaginary, these past and present concerns are equally comprehensible for a non-Chilean spectator.

Gran Sur embraces the production of artists who are culturally and politically committed to the age they live in, and whose importance is still valid today despite the intervening time and distance. This is true for conceptual reasons but also for the acuity of their work in transgressing formats and genres. Los colgados or the hanged ones (as the panels in A Chile are commonly known) are, at once, performance, action, documentation and installation. Art gains in density and breadth, sidestepping censorship while fabricating a coded language, which, in the words of the philosopher Pablo Oyarzún, “stimulates the exploratory deployment of specific operations of the artistic product, which is generally spoken of in terms of the metaphorization of the cultural discourse, and even, in certain cases, efforts to transform modes of artistic production.”1 Adasme believed his message could not be properly conveyed in painting; he represented a generation of artists who subverted the mechanisms of production and who would devote themselves, not to exhibiting objects, but to exhibiting themselves: and so, during the dictatorship in Chile, the individual body became the collective body.

A body that ‘circumvolutes’, like in Catalina González’s work Circunvoluciones ([Convolutions] 2017), a video in which four former political prisoners, Patricia Fuentes, Elena Espinoza, Sandra García and Odessa Flores, physically engage with marks of aerial targets that signal the military occupation. Signs that establish the coordinates within which a target can be eliminated. Art appears wherever life is in danger of disappearing.

Today and Yesterday

Art can also disappear wherever death is in danger of appearing. In Ayer y Hoy ([Yesterday and Today] 2013”, Nicolás Franco quotes from Chile Ayer Hoy, a volume of propaganda published by the military government in which dark, depressing photographs of Chile under the presidency of Salvador Allende are contrasted with colourful and pleasant images of Chile under Pinochet. This might be an innocent exercise whose guilt is uncovered after a process of elimination. Divested of the snapshots, the oppositional game is exposed. Art is not propaganda. But, is it spectacle?

Let’s stir things up and return to yesteryear and the journal Revista Hoy. In its first issue of 1980, an article called “¿Arte o espectáculo?” analysed Para no morir de hambre en el arte (To Not Die of Hunger In Art), an action by C.A.D.A. (Colectivo de Acciones de Arte), a group originally made up of the artists Lotty Rosenfeld and Juan Castillo, the sociologist Fernando Balcells, the poet Raúl Zurita and the novelist Diamela Eltit. The action consisted of the artists distributing milk in a poor area of the city, documenting it on video and in photographs, and then later showing these images together with the containers of milk. The action was a minimal gesture with immense overtones for a country known for extreme inequality. An insert in Revista Hoy showed how these and other actions caught the press flatfooted: “Art critics had to undertake tireless efforts to spot the value of the spectacular in this chaotic panorama.”

Artistic interventions at the time were not simple to understand for anyone who wished to follow the standard path. Nor were they simple for the passive spectator. Six airplanes fly towards Santiago de Chile. They cross the sky but also the border that divides life and art. ¡Ay Sudamérica! (Ay Sudamerica!) is an action by C.A.D.A. from 1981 that recalled the attack on the Palacio de la Moneda. This time the planes did not drop bombs, but flyers with a text claiming: “We are artists, but every man who works for the expansion, even if only mental, of his living space, is an artist.” To make this proposal even more explicit, the group created their best known and most enduring work, No+ (No More), two years later. These are signs that are effectively activated by anyone who wishes to become an artist by means of completing a sentence. When “No+” (no more...) was written on banners and on walls in the public realm the phrase was completed with words like “inequality,” “repression” or “dictatorship”. This formulation of “no more” has lasted until the present day and was in wide use during the protests of October 2019; incredibly, the meanings the phrase engendered most recently used many of the very same words as forty years ago: “inequality”, “repression” and “dictatorship”.

The C.A.D.A. group was well aware that signs are not innocent, and that art is shaped both by context and public participation. One of its members, Lotty Rosenfeld, brought this teaching down to ground level. In her series Cruces sobre el pavimento (Crosses on the Pavement) she makes use of something that already exists, a dividing line, to turn two-way roads into works of art that set off in multiple directions. Her intervention subverts road markings by transforming a line into a cross that marks the spot (you are here, I was here), a Catholic symbol (a burial place), or a satire of modern global architecture (less is more). In every case, her crosses represent a crossing out of power: “Many people will realize that as you cross a given sign, you turn it around, you bring out something that was hidden inside it.”2 Through multiple performances and interventions her crosses join Chile with the White house in Washington D.C., the Arc de Triomphe in Paris, the Plaza de la Revolución in Havana, or Puerta de Alcalá in Madrid. Signs are not innocent, just as the place where the artwork is exhibited is not innocent.

Commercial Art

The original function of the building where Sala Alcalá 31 is located was the headquarters of Banco Mercantil e Industrial. It makes a lot of sense, or more sense, to exhibit the works selected by Hoffmann ́s House here: If I Can Make It Here I Can Make It Anywhere (2007), a work of 144 drawings by 72 Chilean artists, which use bank slips as drawing paper to symbolize the monetary flow of the Banco de Chile, a banking institution that allegedly transferred money illegally from Augusto Pinochet’s accounts to the headquarters of Riggs Bank in New York. These drawings accrue a surplus value by being shown in this particular venue.

Also on exhibit in this same setting are works such as the delicate gloves made of coal by Alejandra Prieto ([Gloves II] 2016), or photographs from the series La Manzana de Adán ([Adam’s Apple] 1986-87), by Paz Errázuriz, creations which are equally informed by the setting in which they are shown. Evelyn, Pilar, Coral, Nirka, Leyla, Deborah, Andrea Polpaico, Maribel, Chichi, Susuki and Macarena, the transvestites portrayed by Errázuriz, their families and the clients who frequented the brothels where they worked, show a joyful, unprejudiced face in an otherwise impoverished, miserable, repressed Chile. The economic crisis the country suffered in 1982 hit the lower classes especially hard. Published in book form in 1989, the series La Manzana de Adán, like the work of many of the artists from the 1970s and 80s, initially did not cause much of a stir. During that period, it seemed as if the Andes mountain range was higher and the Pacific Ocean was wider than they are now.

The future of the country was also conditioned and modified by another force, but this time not of nature: the implementation of neoliberalism in Chile’s economic structure. Since the mid-eighties, Chilean art became commercial in the sense that artists focused their works on the effects of trade and commerce on cities and their inhabitants. Prótesis del Nuevo Éxodo ([Prosthesis of the New Exodus] 2006), by Francisca Benítez, depicts improvised structural additions appended to residential buildings like external tumours, in infinite symmetrical beehive constructions, which one can also see in Gianfranco Foschino’s rendering of everyday moments in Departamentos ([Apartments] 2012), and which take the form of an impossibly fragmented map made of sewn-together strips of cloth in Francisca Aninat’s N 5. Serie Sudamérica ([No. 5. South-American Series] 2015).

Artists like Patrick Hamilton portrayed this species of commercialism in the capital, Santiago, not with oil on canvas, but by extracting layers, shells, urban fixtures or industrial residues and clarifying their context. Critic Guillermo Machuca wrote: “Hamilton and I have long agreed on this: the city is never finished. It is a question of the efficacy of the orthogonal and the vertical. Cities like ours are inhabited by people who move illogically (something which Malevich underscored as his architectural ideal)”3. These words could be perfectly applied to Proyecto Santiago Derivé ([Santiago Dérive Project] 2006-08). The influence of the United States (ranging from the economic infiltration of the Chicago Boys to the cultural influence of U.S. clothing or fast food) adds yet another element of confusion to the identity of a country suffering from historical multiple personality disorder.

A Logos for America

It is time to tell America that it is not the United States. Or, better put, to tell the United States that it is not America, and to do so on a large scale. Over the course of two weeks in 1987, Alfredo Jaar exhibited A Logo for America in Times Square, a sign that simply yet effectively explained that the continent is not just North America but the entirety of the Americas, Chile included. This was ethnocentrism confronted at its very heart by a Gran Sur, a Great South. There are some things that have to be said loud and clear and in huge illuminated letters so that they can be seen from a distance. In Gran Sur (2011) Fernando Prats re-presents the newspaper notice explorer Ernest Shackleton published in 1907, where he advertised for Antartic adventurers, as a massive neon sign: “Men wanted for hazardous journey. Small wages, bitter cold, long months of complete darkness, constant danger, safe return doubtful. Honour and recognition in case of success.” Had they known how the trip was going to turn out, few of those courageous men would have responded to the job offer.

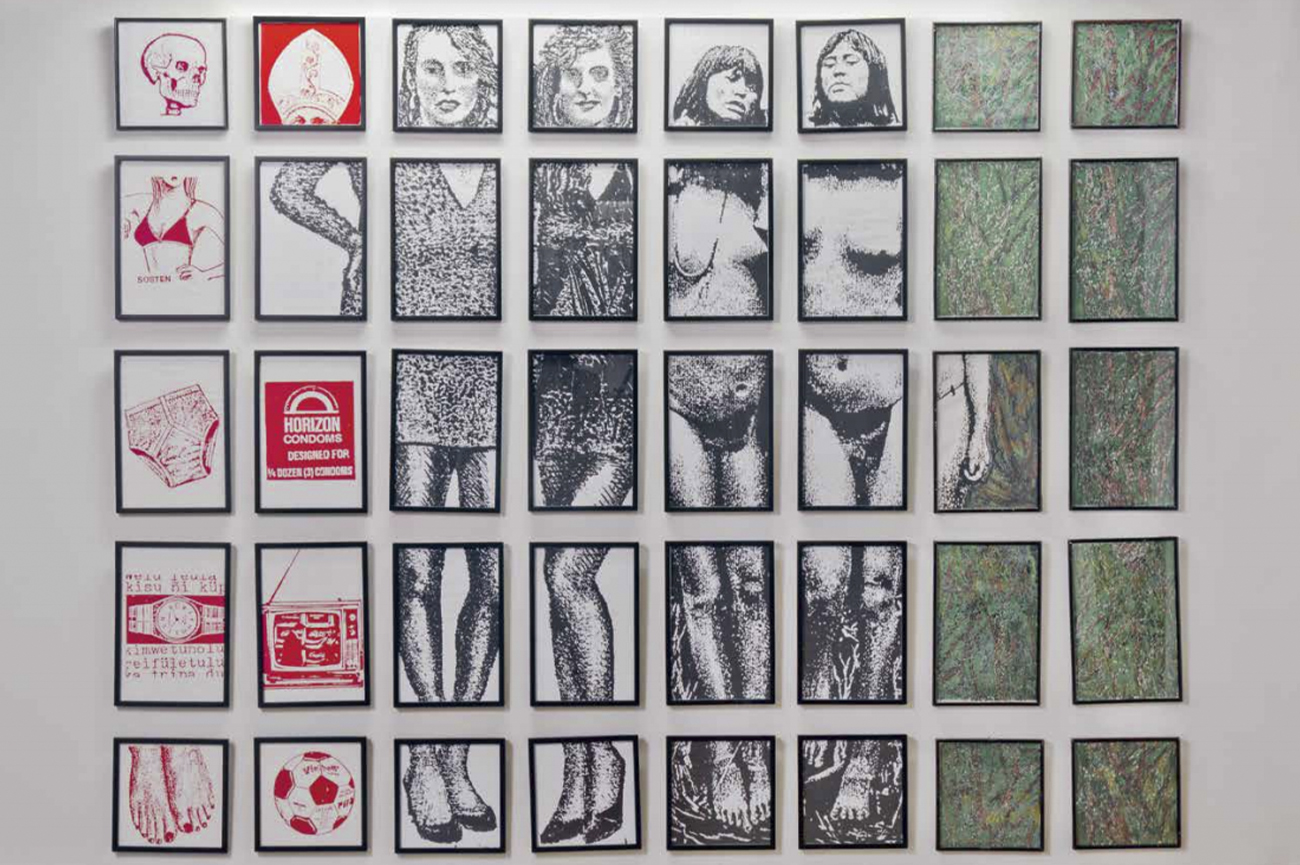

That message can now be seen in Spain, alongside La Balsa de la Medusa ([The Raft of the Medusa] 2015), by Josefina Guilisasti, a tapestry that reinterprets the intra-history of the painting by Géricault—from Romanticism to the fate of the work during the Second World War—by means of an intervention in the content and support of the work, and near Juan Pablo Langlois’s Sin Título de la serie “Misses” ([Untitled, from the series Misses] 1990-95), which are made up of fragments of images of women who took part in beauty contests in dialogue with images of indigenous women, resulting in a woman’s body being dismembered by the Western canon. A canon imposed by force of cannons from the Discovery onwards, which was never redefined following independence from the Spanish crown at the beginning of the nineteenth century.

Maybe it’s better not to remember the past or to conjure up the “fathers of the fatherland”—at least, it may be better to not to let them see us. Andrés Durán brings together half a dozen of these progenitors (including Bernardo O ́Higgins and José Miguel Carrera) by photographing their equestrian statues or their standing figures and subjecting them, via digital manipulation, to censorship by sticking their heads in virtual concrete pedestals—as in the series Monumento editado ([Edited Monument] 2014-17). Victims of idolatry, they are transformed into symbols of abstract power by means of the digitized invasion of concrete. These new symbols turn out to be as intangible as Chile’s own history, as ethereal as the reality of the identity of a country that is still configuring a logos.

The Great Beyond

Perhaps one has to delve into the unconscious, or allow images that coexist and linger in our memory to shape, through association, one single idea of the country (Voluspa Jarpa, El Jardín de las Delicias [The Garden of Earthly Delights], 1995). Or, more directly, to invoke the spirits of the underworld. Can the meeting of psychoanalysts brought together by Natalia Babarovic in her canvas (Reunión de psicoanalistas [Meeting of Psychoanalysts], 2015) be of any help to us? This painting, both in its technique and in its presentation, is similar to an icon, to a piece of wall taken from its place of origin: “Babarovic’s canvases are hung on the wall directly without stretchers or indeed without frames, thus underscoring—ironically and unadornedly—the persistence of a manual painterly gesture that eschews both illusionism as well as anachronism.”4

Arturo Duclos’s tablecloths not only suggest but also seem to actually emerge from some great beyond. They are hieroglyphics, encrypted messages that contain instructions, spells, riddles or warnings that could supplement the teachings represented by the flags presented by Felipe Mujica (Las universidades desconocidas [The Unknown Universities], 2016), these being banners of institutions that suggest communication with other dimensions. Then there is an invocation of the unknown, or of another kind of knowing, in Juan Downey’s work with Amazonian tribes (in the mythical The Laughing Alligator, 1979). And also in the recording of an action by Pilar Quinteros (Lago Bulo [Lake Bulo], 2016) that provides some clues to what lies beyond in a ritual that joins what is alive with what is dead through a videotaped process of destruction, the burning of a scale model.

The decomposition, or scatology, that is coupled with political discourse in Camilo Yáñez’s work (Poética, podredumbre y polyvisión, [Poetics, Putrefaction and Polyvision], 2018-19), or with an aesthetic experience in which the disembodiment of a beached whale is compared with a painting or sculpture lesson (in Musculus, 2018, the video by the collective Museo de Historia Natural Río Seco). What is abandoned, crumbles and collapses is the visual motif of vast canvases by Jorge Tacla and the sinister stop- motion video of Juan Pablo Langlois: in the former, it is the building that crumbles; in the latter, it is the people. There is also a feeling of suspense, of uncertainty, attending the works of Adolfo Bimer and Francisco Rodríguez.

In the current crop of Chilean art there is room for all this and for other perennially latent concerns that are understood or apprehended from other perspectives, like the whiff of dictatorship captured by the lead character of Brisas ([Breezes] 2008), the video by Enrique Ramírez, in the ironic nostalgia for communism contained in Camila Ramírez’s installations, in the grave nostalgia for popular struggle pictured in Rodrigo Valenzuela’s photos of barricades, in the introspective nostalgia for the utopian socialist past in Mario Navarro’s mirrored artifact, in the foregrounding of an improvised and proudly popular aesthetic in the photographs of Magdalena Correa, or in the satirical fable that delineates the confusion between work and leisure instigated by capitalism as seen in Iván Navarro’s bottomless well.

Nature is the motif chosen by Mónica Bengoa in her felt mural Algunas observaciones de mediodía ([Some Observations at Noon] 2012), and in Cristóbal Cea’s video Seguidores del diluvio ([Followers of the Flood] 2018), in the case of the latter with observations about the effects of climate change developed in conversation with the frenetic circulation of images on the internet. All of these ideas and themes animate the leading artworks produced by Chile’s most important contemporary artists today. Individually, they are striking, each and every one of them; together, their display constitutes a big south far removed from our little north that, thanks to this instance, is no longer somewhere out there, but fully here and now.

1 Oyarzún, Pablo (1988). Arte en Chile de veinte, treinta años. Georgia: University of Georgia, Center for Latin American studies, p. 17.

2 Saúl, Ernesto. Balance con signo +. Lotty Rosenfeld. CAUCE, no. 88, Santiago, August 1986, pp. 28-29.

3 Machuca, Guillermo (2018). Astrónomos sin estrellas, Ed Departamento de Artes Visuales Facultad de Artes Universidad de Chile, p. 195.

4 Valdés, Adriana (2006). “A los pies de la letra: arte y escritura en Chile”, in Mosquera, G. Copiar el Edén arte reciente en Chile = Copying Eden. S.L.: Puro Chile, p. 42.

Fundación Engel © 2020

Fundación Engel © 2020